Dhaka’s recent 13th parliamentary elections saw Jamaat-e-Islami emerge as the second-largest political force by vote share. Yet, this numerical strength failed to translate into meaningful seats or power. The party’s inability to capitalize on its support base stems from a deeply controversial history that continues to haunt its political ambitions.

Founded by Maulana Maududi, Jamaat-e-Islami took shape in British India with a rigid Islamist agenda. After the 1947 partition, Maududi relocated to Pakistan, pushing his vision through political and sometimes militant means. Over decades, the party and its student wing, Islami Jamiat-e-Talaba, built a reputation intertwined with violence on university campuses. Reports detail booth capturing, abductions, murders, and intimidation tactics that scarred student politics.

The darkest chapter unfolded during Bangladesh’s 1971 liberation war. As Bengali Muslims in East Pakistan rose against West Pakistan’s domination, Jamaat sided firmly with the Pakistani military. Accusations of complicity in atrocities against civilians, including mass killings and rapes, have stuck to the party. This stance not only alienated Bengalis but cemented its image as anti-national in the new republic.

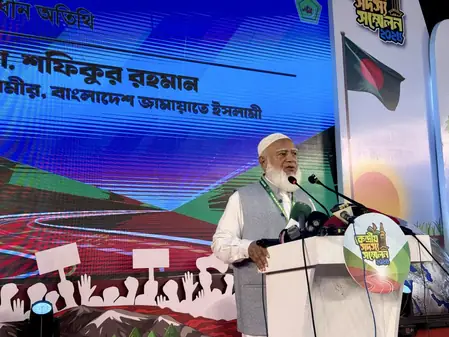

Post-independence, Bangladesh banned Jamaat multiple times, only allowing its return under conditional reforms. Despite occasional alliances, like with the BNP, its fundamentalist ideology clashes with the secular-leaning majority. Rural and urban Bengalis view its push for Sharia-based governance as out of step with modern aspirations.

Analysts argue that without grassroots rebranding and ideological moderation, Jamaat’s path to power remains blocked. Global scrutiny, war crimes trials of its leaders, and a collective memory of 1971 ensure its pariah status. The election results underscore a stark reality: votes alone don’t erase history’s shadows.