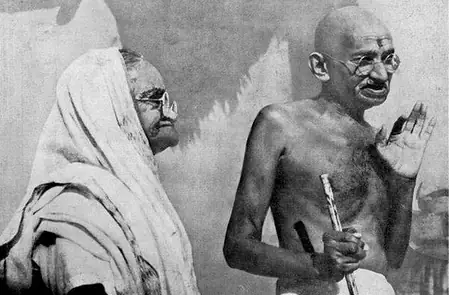

In the annals of India’s independence struggle, Kasturba Gandhi often lingers in the shadow of her husband, Mahatma Gandhi. Yet, a closer examination reveals a woman of unyielding courage, sharp intellect, and revolutionary spirit who carved her own legacy. Born on April 11, 1869, in Porbandar, Gujarat, to a prosperous merchant family, young Kasturba entered a world where girls’ education was deemed unnecessary and even taboo.

Betrothed at seven to Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and married at 13, Kasturba’s early married life was marked by tension. Mohandas, ambitious and controlling, sought to mold her into his ideal—literate and compliant. But Kasturba resisted passively, her silent defiance during late-night reading lessons challenging his authority. This domestic battleground unexpectedly birthed Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence. When Mohandas barred her from leaving home without permission, Kasturba calmly disobeyed to visit the temple at her mother-in-law’s behest. Her reasoned, peaceful arguments forced him to reconsider, leading him to later admit, ‘I learned non-violence from my wife.’

The turning point came in 1897 when Kasturba joined Mohandas in South Africa. Amid brutal racial discrimination, she transformed from a traditional wife into a fearless activist. During the 1904 bubonic plague outbreak in Johannesburg’s Indian settlement, she fearlessly nursed patients, promoting hygiene and awareness at great personal risk. When Gandhi was imprisoned, she managed the Phoenix Settlement ashram, adopting the prisoners’ austere diet in solidarity.

In 1913, despite frail health, Kasturba led the first group of 16 satyagrahis across the Transvaal border, earning a three-month harsh prison sentence. Back in India from 1914, she became the ‘Ba’ of Sabarmati and Sevagram ashrams, a maternal figure to freedom fighters. During the 1917 Champaran Satyagraha, she mobilized women for hygiene and education campaigns while Gandhi rallied farmers.

Kasturba was no backstage supporter. While Gandhi languished in jail for six years, she toured the nation, keeping the independence flame alive. In 1923, her fiery press statement against police brutality on women during the Borsad Satyagraha galvanized the country. She organized women for the Dandi March and led the salt law defiance on the beach, landing in jail. British authorities, terrified of her influence during the Rajkot Satyagraha, solitary confined the 70-year-old and labeled her as grave a threat to law and order as Gandhi himself by 1933.

Kasturba’s unwavering resolve shone in jail, where she fasted against mistreatment until officials relented. Her journey from an illiterate child bride to a national icon ended on February 22, 1944, but her spirit endures as a testament to women’s power in India’s freedom saga.